On March 4, 2023, Ascension Music presents “Sacred Dialogues,” the latest installment in our Salon Series: a concert of cantatas by one of Baroque France’s premier composers, Élisabeth-Claude Jacquet de la Guerre (1665-1730). We offer this program in Women’s History Month, as an opportunity to explore the compositions of a remarkable woman. The program is also a devotional offering for Lent. Jacquet de la Guerre’s Cantates françaises sur des sujets tirés de l’Écriture (French Cantatas on Biblical Subjects) offer an expressive and unique perspective on stories from the Bible - with texts and music that aren’t afraid to speak truth to power.

In this post, we’ll meet this lesser-known but masterful composer. Later this week, we’ll explore the concert’s cantata repertoire in a second post.

Portrait of Élisabeth-Claude Jacquet de la Guerre by François de Troy (1645-1730)

Part I: The Composer and Her Music

Élisabeth-Claude Jacquet was born into a family of harpsichord makers during the reign of Louis XIV, the Sun King. It was an era when national taste was dictated by the culture at court, where Louis danced ballets by his favored court composer Jean-Phillippe Lully, and where artistic success often hinged upon finding the right powerful supporters.

The Jacquet family, being of the artisan class, educated all their children (daughters included) for careers in the arts. Élisabeth was a singer and a harpsichordist, and the thoroughness of her training was evident when she played for the King at the age of five. Louis XIV credited himself with “discovering” her as a brilliant new prodigy.

Unlike some prodigies, however, Élisabeth did not dive immediately into a miniature adult career. Between a few court appearances, she remained with her family until around the age of 12, when she joined the court of Madame de Montespan, the King’s favorite mistress. In the culture of Versailles, such an appointment was a fortuitous position for a young woman. Élisabeth Jacquet began composing for the court of Louis XIV, as well as performing as a remarkable harpsichordist, and learning the cultural politics of seventeenth-century France as a member of Madame de Montespan’s retinue.

At the age of 20, Jacquet left Versaille to marry the Parisian organist Marin de la Guerre, another member of a prominent working-class musical family. For the rest of her career she preferred to use both her maiden and married names in publications. Jacquet de la Guerre enjoyed a successful career in Paris as a teacher and performer. The home she shared with Marin included a music room where she likely performed, collaborated, and entertained friends, in gatherings which, though humbler than those of the aristocratic salon hostesses of her time, might have resembled our own Salon Series gatherings.

Jacquet de la Guerre also flourished as a composer. Thanks in part to her court connections, she had the opportunity to compose many large-scale works, including a ballet, and the first French opera by a woman, Céphale et Procris. Her keyboard suites are virtuosic works that display her mastery of the instrument, and one of her final compositions was a Te Deum commissioned to celebrate Louis XV’s recovery from a deadly illness. Reviews in journals of her time show that her contemporaries regarded her as a professional and gave her works a hearing as such.

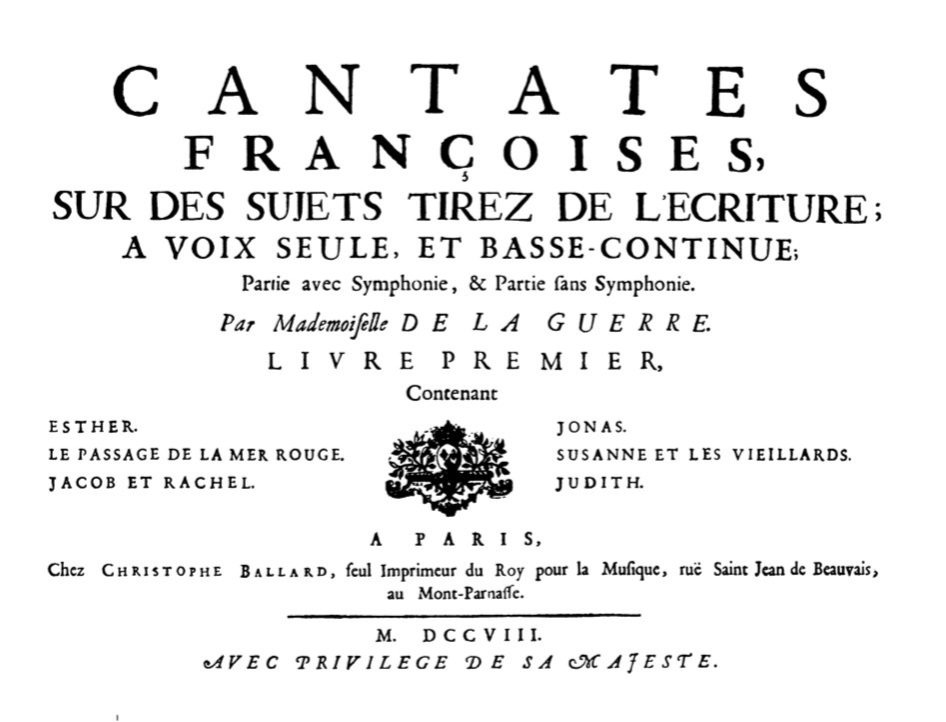

Though professionally successful, Jacquet de la Guerre’s life was not without tragedy. She had one child, a talented harpsichordist like his parents, who died at the age of ten. Her husband passed away in 1707, after 23 years of marriage. Her income reduced, Jacquet de la Guerre moved to a smaller home, and gave renewed attention to composition and publishing. One of the first major works she produced after this transition was her first volume of French Cantatas on Biblical Subjects.

The cover of Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre’s first volume of French cantatas (Paris, 1707)

The Cantatas

Jacquet de la Guerre’s three-volume collection of French Cantatas are chamber works intended for court performance. The first two volumes, both collections of sacred cantatas, are, like most of her works, dedicated to King Louis XIV. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was customary to dedicate major publications to aristocrats and rulers, who would often return the compliment with a gift of money. Bach, Vivaldi, and all your favorite Baroque composers did the same. The obsequious dedicatory paragraphs at the beginning of these works read very strangely today, but in an age of absolutism, when musicians were considered a servant class, it was a necessary professional tactic.

The King’s favor was especially important for Jacquet de la Guerre’s cantatas, for they were an innovative genre in 1707. The cantata, a nonstaged narrative work for voice and a few instruments, was a recent invention from Italy. One of the first known French composers to adapt this genre to the French language was Nicolas Bernier (1664-1734), who published a collection of cantatas in French in 1703. Musical styles imported from Italy were often unpopular in Louis XIV’s France - his favorite composer, Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), had almost single-handedly established a French style that dominated music long after the composer’s death. Jacquet de la Guerre was taking an artistic risk by working in the newfangled, foreign Italian style. Furthermore, she was taking the cantata in a direction Bernier had not tried: her cantatas explored sacred themes.

Portrait of Françoise d'Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon, by Pierre Mignard I (1612–1695)

This turned out to be a canny choice. By 1707, Madame de Montespan had been supplanted in the King’s affections by a new mistress, the Marquise de Maintenon. Louis XIV was so taken with her that he actually married her in a secret ceremony, despite the couple’s class differences. The Marquise was a deeply religious woman who influenced the Court to pay more attention to matters of faith. Jacquet de la Guerre’s dramatic sacred cantatas, written for performance in court, not in church, were a perfect fit for the current culture of Versailles.

Considering the Marquise’s influence, it is interesting how many cantatas in Jacquet de la Guerre’s collection focus on women of the Bible. In Volume 1, Rebecca, Judith, Susanna and Esther all appear. The biblical story of Esther in particular explores themes that could have resonated with the Marquise: an absolutist King, Ahasuerus, who is both feared and loved by the many women in his life; his queen, Esther, who risks her life, breaking royal protocol to intercede for truth and justice.

In an era of absolutism, one might expect this cantata to step carefully around the idea that kings can be influenced or criticized. However, the text of Jacquet de la Guerre’s Esther doesn’t shy away from exhorting kings to pursue justice and listen to the righteous influences in their lives. We’ll dive into these themes later this week in Part II: Esther, Truth, and Justice.

Sources for Further Reading

Beer, Anna. Sounds and Sweet Airs: The Forgotten Women of Classical Music. UK: OneWorld Publications, 2016.

Cessac, Catherine. "Jacquet de La Guerre, Elisabeth." Grove Music Online. 2001; accessed February 25, 2023. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000014084.

Hopkins Porter, Cecilia. Five Lives in Music: Women Performers, Composers, and Impresarios from the Baroque to the Present. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012.