“The Advantage of Artists”

Portrait of Fanny Mendelssohn by Wilhelm Hensel (1829)

In 1841, the composer Fanny Hensel (née Mendelssohn-Bartholdy) presented her husband Wilhelm with a remarkable Christmas present: a cycle of thirteen short pieces for piano, entitled Das Jahr (The Year). The cycle contains one piece for each month of the year, and closes with a postlude.

In 1841, Fanny Hensel had written to an artist friend about her project:

“I’m engaged on another small work that’s giving me much fun, namely a series of 12 piano pieces meant to depict the months; I’ve already progressed more than half way. When I finish, I’ll make clean copies of the pieces, and they will be provided with vignettes. And so we try to ornament and prettify our lives–that is the advantage of artists, that they can strew such beautifications about, for those nearby to take an interest in.”

Quoted and translated in R. Larry Todd, Fanny Hensel: The Other Mendelssohn (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 275.

Self-Portait by Wilhelm Hensel (1829)

The vignettes were to be provided by Hensel’s husband, Wilhelm Hensel, who was the Court Painter to the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III. Fanny Hensel had created a manuscript of Das Jahr with space left at the top of each movement for Wilhelm to add illustrations. She also selected a quotations from German poets to precede each movement.

The result was a unique collaboration by two sensitive artists, working together to “strew beautifications,” to use Fanny’s self-deprecating phrase. The Hensels clearly valued their creation as more than just a “beautification,” for they preserved it carefully in a bound volume. Despite their efforts, this unique work was lost after Fanny Hensel’s lifetime, and was not rediscovered until the late 1980s. Today, you can peruse a complete facsimile of Fanny and Wilhelm Hensels’ bound and illustrated Das Jahr.

Listening to Das Jahr

Das Jahr is a set of character pieces, a popular nineteenth-century genre. Character pieces are short works, often for piano, often with programmatic content: they tell a story or paint a picture. Because Das Jahr includes actual texts and pictures accompanying each character piece, we receive a uniquely nuanced glimpse into the composer’s imagination while we travel through this musical year.

No. 1, January: A DREAM

Ahnest du, o Seele wieder

Sanfte, süße Frühlingslieder?

Sieh umher die falben Bäume!

Ach, es waren holde Träume!

– From “Im Herbste” by Johann Ludwig Uhland

Can you again foresee, o soul,

The soft, sweet songs of spring?

Behold, all around, the fallow trees!

Ah, there were lovely dreams.

Hensel’s performance direction for this piece is Adagio, quasi una Fantasia. Typical of the genre fantasia, the music explores a variety of moods in a style reminiscent of improvisation. The movement opens with a somber, descending motive in the bass of the piano, which returns periodically to bind the movement together. Musicologist Christian Thorau has found echoes of this initial motive throughout the entire cycle: this whole musical year finds its source in the January movement.

Wilhelm Hensel illustrated this movement with a portrait of Fanny, perhaps as St. Cecilia or a Greek muse, holding a lyre and dreaming of angels. Musicologist Larry Todd has suggested that Wilhelm could be framing the whole cycle as Fanny’s musical dream.

No. 2, February: Scherzo

Denkt nicht ihr seyd in deutschen Gränzen

Von Teufels-, Narren- und Todtentänzen;

Ein heiter Fest erwartet euch.

– From Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Think not that you are within German borders;

A bright festival of devils’, fools’, and deaths’ dances

Awaits you.

February is preceded by a quotation from a Carnaval scene in Goethe’s Faust. In 1841, the Hensels visited Rome for the wild, pre-Lenten festival of Carnaval–something like New Orleans’ Mardi Gras. This movement may reflect their Carnaval experience. Fanny’s sprightly, fantastical music uses the 6/8 rhythm of the tarantella, a frantic Italian dance. Punctuated with unexpected pauses and changes in tonality, one could imagine masked figures appearing and disappearing through the streets of Rome. Wilhelm’s illustration hints at the romance of the atmosphere: it shows a masked couple in Renaissance garb, drifting through the streets amid whirling dancers.

No. 3, March

Verkündigt ihr dumpfen Glocken schon

Des Osterfestes erste Feyerstunde?

– From Goethe’s Faust

Do you muffled bells already

Proclaim the first solemn hour of Easter?

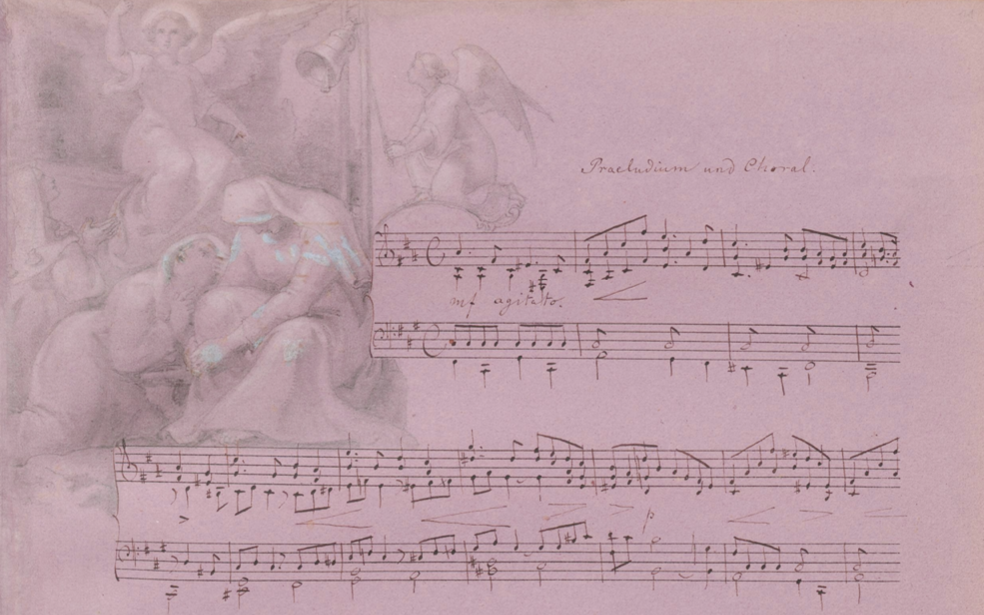

Fanny Hensel labels this piece Preludium und Choral, making it a Romantic, pianistic reworking of a Baroque liturgical organ genre associated with Johann Sebastian Bach. Both Fanny and her brother Felix were dedicated students of Bach’s music.

This movement begins in an agitated f minor, with relentless ostinato eighth notes. It grows in intensity until it gives way to simple statement of the Lutheran Easter chorale, Christ ist erstanden. After the chorale enters the piece, the music grows in energy and joy until concluding in a triumphant C-sharp Major–quite a harmonic distance from its opening key. The movement’s journey from darkness to light reflects both the liturgical progression through Holy Week to Easter, and the seasonal progression from winter into spring.

Wilhelm’s vignette for this movement emphasizes the work’s spiritual dimension. He depicts Mary Madgalene, Mary of Cleopas, and Salome, the three women who discovered Christ’s empty tomb in the biblical narratives. The women are greeted by one angel (who looks a lot like Fanny Hensel), while a second angel rings a bell–a reference to the Goethe quotation.

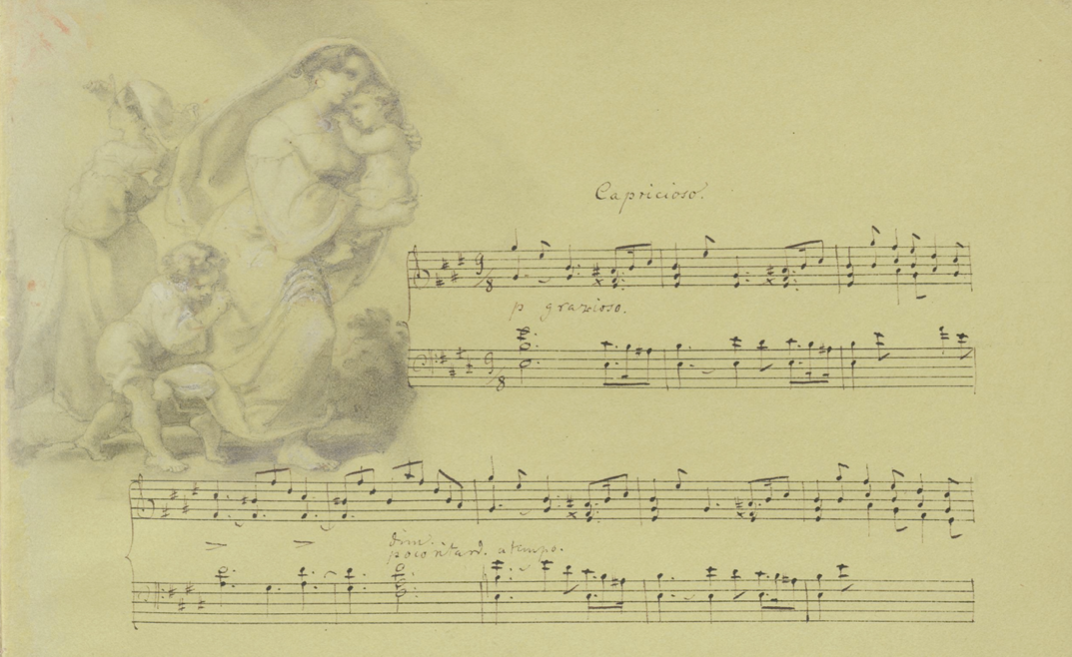

No. 4, April: Capriccioso

Der Sonnenblick betrüget

mit mildem, falschem Schein.

– From “März” by Goethe

The sunshine cheated us

With mild, false light.

Following the dramatic journey of March, in April we find a lighter work: indeed, a capricious one, as indicated by its subtitle. The poetic quotation pokes fun at the ever-changing weather of April. Fanny Hensel depicts the “cheating sunshine” with a graceful, dancelike theme in 6/8 time, playfully contrasted with exuberant, chromatic passages. Wilhelm’s illustration shows a mother covering her head and rushing indoors with her children to avoid the rain, while a second woman gazes at the sky.

No. 5, May: Spring Song

Nun blüht das fernste, tiefste Thal.

– From “Frühlingsglaube” by Johann Ludwig Uhland

Now the farthest, deepest valley is in bloom.

Fanny Hensel subtitled this movement “Frühlingslied” (Spring Song), a title used more than once by herself and her brother, Felix Mendelssohn. Both siblings composed vocal songs with this title, but most famous is Felix’s Song without Words Op. 62, No. 6, a “Frühlingsleid” for piano. Fanny Hensel’s Frühlingslied paints a varied picture of spring’s moods, by turns playful, graceful, poignant and even stormy–there’s a moment of rapid sixteenth-notes in the bass which sounds like faraway thunder.

Wilhelm chose to illustrate the movement’s carefree moments. His drawing shows a girl in Arcadian dress showering a boy with flowers.

no. 6, June: Serenade

Hör ich Rauschen, hör ich Lieder,

Hör ich holde Liebesklage?

– From Goethe’s Faust

Do I hear rustlings, do I hear songs,

Do I hear the sweet lament of love?

As you may have noticed by now, each movement in the Hensels’ Das Jahr volume is inscribed on colored paper. For June, a light blue was chosen, likely to emphasize the evening mood of this Serenade. The style is that of the Song without Words genre so favored by Fanny Hensel and her brother. The Mendelssohns’ Songs without Words were not unlike the lyrical bel canto opera arias so popular in the early nineteenth century. Emphasizing the romantic image of a serenading lover, the second section of Fanny Hensel’s score indicates that the music is to “imitate a guitar.”

Wilhelm Hensel’s illustration shows a sweet, possibly Italian scene, in which the serenading lover with his guitar looks suspiciously like Wilhelm, and the lady in the balcony is a portrait of Fanny.

no. 7, July

Die Fluren dürsten

Nach erquickendem Tau, der Mensch verschmachtet.

– From “Der Abend” by Friedrich Schiller

The meadows thirst

For livening dew; people are languishing.

For the month of July, Fanny Hensel explores the suffering that summer’s heat can bring. For inspiration, she chose a Schiller quotation about drought and exhaustion. Interestingly, her brother Felix would also explore drought, heat, and suffering through music only a few years later in his oratorio Elijah. In the Old Testament books of 1 and 2 Kings, the prophet Elijah proclaims a drought as judgment on corrupt leaders of Israel. Felix Mendelssohn would complete his musical setting of the story in 1846, but he had been contemplating the topic since 1830, so it’s possible that he and his sister discussed ways to express this particular kind of suffering through music.

Fanny Hensel’s music for July opens with lethargic chords in a downward chromatic progression. Falling chromatic lines had been appearing in music as shorthand for impending death since the Baroque–one famous example is “Dido’s Lament” from Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. Hensel then develops this theme atop increasingly swift and agitated rhythms, creating a sense of growing desperation until the movement peters out in quiet sorrow.

To hear Felix Mendelssohn’s musical interpretation of drought, listen to the overture to Elijah. You’ll hear a few family resemblances, including descending chromatic lines and an escalating rhythmic drive.

Wilhelm’s illustration for July seems to turn in a biblical direction as well: the lady in the foreground looks like she could be an Old Testament heroine. In fact, she looks something like Wilhelm’s 1836 painting of Fanny as the Old Testament prophetess Miriam.

no. 8, AUGUST

Bunt von farben

Auf den Garben

Liegt der Kranz.

– From “Das Lied von der Glocke” by Friedrich Schiller

Bright with color

Upon the sheaves

Lies the garland.

This movement begins with the piano imitating a set of trumpet calls. We hear a forte opening blast, followed by a piano response–perhaps it depicts a faraway trumpeter answering the first. The fanfare expands throughout the range of the keyboard, then its dotted rhythms develop into a cheerful march. Wilhelm’s illustration shows us the harvest procession hinted in Fanny’s music: in the foreground, women bearing garlands and sheaves of wheat, and in the background, the alphorn player who has called the community to celebrate.

NO. 9, SEPTEMBER: The River

Fließe, fließe, liebe Fluß,

Nimmer werd’ ich froh.

– From “An dem Mond” by Goethe

Flow, flow, dear river;

I shall never be happy.

The subtitle of Fanny Hense’s September is “By the River.” For inspiration, she chose Goethe’s “To the Moon,” a poem exploring memory, loss, and the passage of time through the image of a ceaselessly flowing river. Franz Schubert would later create two settings of this evocative poem. Hensel interprets Goethe’s imagery through a texture of delicate, incessant sixeteenth notes running throughout the movement’s constantly shifting harmonic territory. The sensitivity and athleticism demanded by this movement gives us a hint at Fanny Hensel’s expert pianistic technique.

Wilhelm’s illustration (which could well be another portrait of Fanny) shows a pensive female figure in Greco-Roman dress, gazing at a flowing river which melts into the figurative river of Fanny’s sixteenth notes.

NO. 10, OCTOBER

Im Wald, im grünen Walde,

Da ist ein lustiger Schall.

– From “Die Spielleute” by Joseph von Eichendorff

In the forest, the green forest,

There is a merry sound.

Like the movement August, October evokes an instrument other than the piano: this time, horn calls. The movement’s motto quotation is from a poem by Eichendorff called The Minstrels, in which a horn blast travels through field, valley, and forest to announce the arrival of itinerant musicians. Fanny Hensel’s music evokes horns echoing through the landscape, sometimes near, sometime farther away. This vigorous movement is full of the fifths, fourths, and arpeggiated overtone series typical of the natural horn.

Wilhelm’s illustration shows our horn player on cliff above a forest, causing some upset to a couple of deer. Though the poem describes horns announcing the arrival of minstrels, it is understandable that these creatures would be reminded of hunting horns instead!

NO. 11, NOVEMBER

Wie rauschten die Baüme so winterlich schon

Es fliehen die Traüme des Lebens davon

Ein Klagelied schallt

Durch Hügel und Wald.

– From “Trauer” by Ludwig Tieck

The trees are already rustling as though it is winter,

The dreams of life are fleeing away,

A song of sorrow sounds

Through hill and woodland.

In Fanny Hensel’s poetic quotations for Das Jahr, we have already seen several poems that reference music: bells in March, horns in October, and “songs” in January, July, and now November. Hensel’s Ludwig Tieck quotation for November is a darker echo of the October quote: again we read of music traveling through a changing landscape, but now, instead of an expectant horn call, a “Klagelied” (song of sorrow) sounds through hills and woods. In Fanny’s musical setting, you’ll hear this “song” in a chorale-like opening theme, which travels through a disquieted musical landscape of “rustling” eighth and sixteenth notes.

Wilhelm Hensel’s illustration is rather gothic, depicting a monk pausing to lament while digging a grave. The image suggests both at the Feast of All Souls, celebrated on November 2, and at the death of the old year as autumn turns to winter.

No. 12, December

Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her.

– From a hymn by Martin Luther

From heaven high, I come to you. (Trans. Winfred Douglas)

The cycle’s penultimate movement begins with swift, light figures depicting a snowfall. This virtuosic flurry gradually slows and diminishes into a simple iteration of Martin Luther’s Christmas hymn, Vom Himmel hoch (with a little bit of pianistic snowfall scattered between the phrases of the melody). After a second, triumphant, bell-like appearance of the chorale, the music gently fades away.

Wilhelm’s illustration contains one last image of Fanny: this time, she appears as an angel, carrying a baby down from Heaven. The baby is both a reference to the Christ Child, and also likely a portrait of Fanny’s and Wilhelm’s son, Sebastian.

13. Postlude: Chorale

The final movement of Das Jahr is labeled Nachspiel, or Postlude. This movement bears neither a quotation nor an illustration. Instead, it tells its extra-musical message simply through Fanny Hensel’s use of the New Year’s chorale, Das alte Jahr vergangen ist (The Old Year is Past). This tune appears as in Bach’s Orgelbüchlein, a collection which forms another example of a musical year: it contains chorale preludes for each season in the liturgical year. In fact, the other two chorales Fanny Hensel used in Das Jahr also appear in the Orgelbüchlein, but this final setting is the most overtly neo-Baroque in style. By cleverly transforming the Baroque genre of chorale prelude into a chorale postlude, Fanny Hensel creates a retrospective on her musical year and her musical influences, while making the genre her own.

The old year now hath passed away;

We thank Thee, O our God, today

That Thou hast kept us through the year

When danger and distress were near.

– From Das alte Jahr vergangen ist, by Johann Steuerlein (trans. Catherine Winkworth)

For Further Reading

Bar-Shany, Michael. “The Roman Holiday of Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel.” Min-Ad: Israel Studies in Musicology Online 5 no. 1 (2006). Accessed September 17, 2020. https://www.biu.ac.il/HU/mu/min-ad/06/Fanny_Mendelssohn.pdf.

Hensel, Fanny. Das Jahr. Liana Serbescu, ed. Kassel: Furore Verlag, 1989.

_. Das Jahr. Reproduction of manuscript from Staatsbibliothek, Berlin (MA Ms. 155). IMSLP: Accessed February 27, 2021. https://imslp.org/wiki/Das_Jahr%2C_H.385_(Hensel%2C_Fanny).

Kimber, Marion Wilson. “Fanny Hensel’s Seasons of Life: Poetic Epigrams, Vignettes, and Meaning in Das Jahr.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 27, no. 4 (2008), 359-395.

Lee, Kyungju. “Fanny Hensel’s Piano Works: Opp. 2, 4, 5, and 6.” DM diss., Florida State University College of Music, 2008. Accessed September 17, 2020. https://fsu.digital.flvc.org/islandora/object/fsu:181518/datastream/PDF/view.

Todd, R. Larry. Fanny Hensel: The Other Mendelssohn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

–. Mendelssohn: A Life in Music. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Toews, John E. "Memory and Gender in the Remaking of Fanny Mendelssohn's Musical Identity: The Chorale in "Das Jahr"." The Musical Quarterly 77, no. 4 (1993): 727-48. Accessed September 17, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/742356.

Except where noted, all poetry translations are by Emma Riggle.